The Astral Body

Subtle Bodies: A Brief Primer #2

In the previous post I spoke on the importance of having a map of subtle bodies. Not only because it plays a deeper role in providing a context for making sense of our experiences, but also because it:

“opens up new realms of experience that would otherwise be passed over, unnoticed.”

I then briefly turned to describe the Prāṇa, Qì, Pneuma or Etheric, all of which refer to the domain of “life-force.” It is the subtle body layer that looks after the most organic, digestive and regenerative processes of the body, but also ranges into highly refined layers that relate to memory impressions, imagination, and thought from the Astral worlds, of which this post will have more to say about. Let us also recall that unlike stacked layers of filo pastry, using the analogy of water in a sponge I explained how subtle bodies are interpenetrated.1 To extend the analogy further, if we regard water soaked through a sponge as corresponding to the Prāṇamaya Kośa (‘the envelope of life-force’, Qì, Pneuma, or Etheric Body) permeating the Annamaya Kośa (or ‘envelope made of food’, or Physical Body), the air which subtly permeates the water is the Manomaya Kośa, or subtle layer referred to as the Astral Body in the Four-Fold Model.2 Using the terms provided by the Four-Fold Model from Table of Subtle Body Correspondences introduced in the previous post, the Etheric Body permeates

and extends beyond what we experience as the sensory domain of the Physical Body, meaning entire regions of the Etheric life-world do not possess any sensory-physical counterpart. Likewise, the Astral Body permeates the Etheric Body and extends beyond its boundaries; there are Astral worlds (worlds of consciousness) that do not possess direct counterparts in the either the Etheric or Physical domains.

Manas & the Astral Body

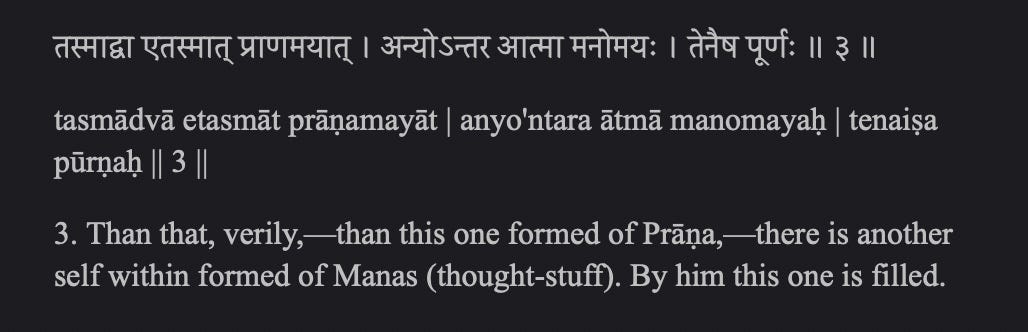

The Astral Body is the layer or vehicle in which the consciousness of emotions and the processes of thought occur. The excerpt above from the Taittirīya Upaniṣad (II.3) speaks of the Manomaya Kośa, from which we can make the following chain of associations. The Sanskrit term Manas — which, as the translation states, means “thought-stuff”— is equivalent to what is usually meant by the word ‘mind’. When we speak, then, of the mind or Manas, we are referring to the Astral Body.3 Mind, of course, is a word that is often used to carry many other meanings, particularly within spiritual traditions. For instance, in the stream of traditions that flow from the Yogācāra school of Buddhism, everything is Mind. In this sense Mind and consciousness are pretty much equivalent terms.4

If, however, we keep to the usage exemplified in the pañchakośa model, wherein the Manomaya Kośa refers to “thought-stuff,” we can make the following experiential distinction: it’s the layer of consciousness we are most familiar with when preoccupied by our thoughts, or caught up in our emotional reactions. Visit the About Sourcing page of The Beyond Within, and you will read that the “ordinary mind” — as in the Manas layer of our subtle constitution — is the layer of consciousness in which our saṃskāras are found.

Saṃskāras

Saṃskāra is a Sanskrit term that is of central importance to yogic psychology.5 It can be translated as “latent impression,” and refers to the imprints left behind by the experiences we undergo. The more intense the experience, the stronger the impression engraved into the psyche, conditioning the mind. When we experience getting carried away by trains of thought, or bodily agitations that hijack our awareness in meditation, or when our buttons get pushed and we experience ourselves veering into states of emotional reaction, we are at the mercy of our saṃskāras; past impressions lying beneath the surface which drive the activity of the manas/mind.

In other words, in its ordinary condition the Astral Body is constituted by our saṃskāras. In effect, the vast constellation of our saṃskāras are what impart to us our sense of personality, attractions and aversions, tacitly held beliefs, and how we perceive ourselves and the world. Consequently, while it may be surprising to us as modern people whose views are deeply shaped by the modern imaginary, the level of ordinary mind in which many people consider themselves to be the most awake, is, according to the Yogic model, the most asleep. Because it’s the layer in which our thoughts, emotions, and actions are reflexively dictated by past conditioning.

That which is which is to all creatures a night, is to the self-mastering sage their waking; that which is waking to all creatures, is a night to the sage who sees.

— Bhagavadgītā 2.69

There will be much more to say about saṃskāras and how to understand their role both in life and in meditation practices in posts to come. Suffice it to say for now, that although an experiential understanding of saṃskāras is pivotal to a well-informed practice of meditation, knowledge of them is yet curiously absent from almost all modern discourse around mindfulness and meditation. Divorced from the originating context within which contemplative practices have been developed, modern mindfulness emphasises many of the benefits of meditation, but is often ill-equipped to cope with the kinds of emotional charges that can, and inevitably will arise when saṃskāras are triggered.

The Astral Body as Sūkṣma Śarīra

Given that the Astral Body is the body of thoughts and emotions (saṃskāras) — what we refer to when we speak about the mind — for all practical purposes it makes sense to speak of it in terms of Manas. But, it’s not the only sense in which it may carry meaning. As I wrote in Subtle Bodies: A Brief Primer #1:

“The term ‘subtle body’ is a standard english translation of the Sanskrit term: sūkṣma śarīra”

As Sūkṣma Śarīra, in its broadest sense the Astral Body can also be used to mean vehicle of consciousness. In common English terms we might say that this distinction loosely corresponds to soul.6 Across multiple traditions both east and west, however, the wide palette of closely associated meanings entailed by ‘soul’ and ‘subtle body’ are complicated and multifaceted. Keeping things simple, then, I invite you to notice that in the Table of Subtle Body Correspondences the Astral Body in the Four-Fold Model also includes the Vijñānamaya Kośa from the pañchakośa model.

Beyond Saṃskāras

Just as we saw with the other subtle body layers, in the forgoing excerpt from the Taittirīya Upaniṣad (II.4) the Manas layer — the layer that consists of saṃskāras — is in turn permeated by the Vijñānamaya Kośa. If you look it up you’ll find that it is usually translated into English as the envelope of ‘discernment’ or ‘discerning knowledge’, but these terms are woefully misleading when it comes to capturing what Vijñāna actually gestures towards, because there really is no modern equivalent. Vijñāna refers, indeed, to a form of knowingness or understanding, but it is not the explicit product of rational deliberation which is the result of the activity of Manas. Rather, beyond the screen of rationality, it is an implicit knowing that is closer to the direct felt-sense of experiencing; or direct experience of spiritual realities akin to the Greek term gnōsis meaning knowledge of the heart, or knowledge by identity. That is to say, we can make a clear distinction between feeling as opposed to emotion.

Permeating the conditioned layer of saṃskāras, then, lies a more subtle level of our being that possess the potential for opening, understanding, and self-transformation. Let’s explain this in experiential terms. For the vast majority of people, the confronting fact is that for most of their emotional life, from the relatively insignificant to the most intense, the mechanical process of saṃskāric reactions predominates; a reflexive sequence from stimulus, to saṃskāra, followed by reaction. But, sometimes, there are occasions where one experiences an ‘emotion’ that comes, so to speak, with a different frequency; like a light that arises from somewhere deeper within. It is not the puppet-like mechanical stimulation of a saṃskāra; not something triggered; not something that compels us to react, screaming to be expressed. Rather, it comes from a place of inner spontaneity, that both radiates and brings us in touch with our essential Being.

“The condition of our soul will change only when our spiritual understanding of our place in nature and cosmos becomes inwardly alive. It can change only when the same feeling and perception that lives in Love accompanies the act of knowing.”

– Rudolf Steiner (February 18, 1923)

Emotion vs Feeling

As the word ‘emotion’ suggests it is an ‘e-motion’ or ‘ex’ as in outward, and ‘motion’ as in movement; precisely that which takes you outside, or away from yourself. But, according to the distinction being made here, feelings arise when we are inwardly moved and possess an entirely different causality. This is a big topic that will have to be spoken of in much greater detail in future posts. But for now, the general indication in terms of spiritual practice is clear.

“If nothing supersensible exists, then there is no source from which moral impulses can be drawn. For no matter how lofty are our ideals, they are simply smoke and mist.”

– Rudolf Steiner (February 16, 1923)

Emotions tend to be predictable, formulaic and easily replayed; like a caricature that can very easily turn into its opposite. Emotions are conflicted and disperse our lives in disparate directions, and ultimately leave us feeling empty. Emotions separate you from the situation or person that trigger them; your essential being is kept from being present. On the other hand feelings come with a sense of plenitude; they centre and unify, creating a sense of unity between you and the person or object to which they are related. Feelings are entirely beyond the domain of rational logic. While the Manas can certainly act to block them, feelings can neither be controlled nor fabricated by it. An essential part of any spiritual path, then, is learning how to discern between that which comes from a reaction and that which doesn’t. And in the cultivation of yogic vision, or sūkṣmadṛṣṭi — super-sensible experiencing — that is exactly what one develops.

The Transformed Astral Body

Given what has been said above, as the seat of feeling the Vijñānamaya Kośa is the subtle layer of the Astral Body through which the our essential Being cognises the world and finds expression.7 On the whole, it is a layer that remains widely undeveloped in human beings. In terms of inner alchemy, then, enlightenment begins when the Astral Body in its initial disparate and conflicted condition is replaced by this ‘new’ layer, and thereby transformed (or transubstantiated) into a unified and illumined vehicle that radiates the indestructible nature of divine being, akin to the paramam vapuḥ of the Upaniṣads, the vajrakaya of Tibetan Buddhism, or the glorious body of the Christian tradition.

A Few Final Remarks

This post is the end result of a lot of draft work in which at least three times the amount of material has been cut. I didn’t even get around to answering one of the questions I wanted to answer. The question: why is it called the ‘Astral Body’? There are, in fact, a lot of good reasons and indications that the term illuminates, including its relationship to animals and what makes us human, the cosmology of the Greeks and its influence in Hermetic traditions of inner alchemy, and as such, astrology and the zodiac. But I will save the details for a future post lest this one become far too long.

The sponge analogy is borrowed (and modified) from Max Heindel’s Rosicrucian Cosmo-Conception; an alchemical treatise positioned within the Hermetic milieu.

The symbolic link in traditions of alchemy between water and the Etheric Body, and between air and the Astral Body is one that runs much deeper than mere analogy. But this is an in-depth and far ranging topic beyond the scope of this Substack post.

In fact, the latin term mens from which ‘mental’ and ‘mind’ are derived, is itself derived from the Sanskrit Manas.

In Sanskrit consciousness is Cit.

Of course, the Yogic texts in which saṃskāras are described do not self-apply any term from which we may arrive at the translation “psychology.” Modern distinctions between yoga, philosophy, psychology and even medicine and healing simply didn’t exist.

An often maligned term in the reductive parlance of the modern imaginary and some modern Buddhists, who isolate the term soul within purely speculative ontological discourses, asserting the philosophical doctrine of anattā, or non-selfhood. In other words, treating the term as an object of rational belief (incidentally, the kind of activity that occurs entirely within Manas). What is under discussion here need not contradict one’s belief in anattā, however. Indeed, in Buddhism vijñāna — which I discuss below — is often translated as ‘consciousness’ (one of the five skandhas or aggregates), and considered by many Buddhist traditions as the continuum or stream that is reborn.

Pertaining to the Higher Self in the Four-Fold Model, broadly corresponding to the divine level of spiritual worlds and beyond. The Vijñānamaya Kośa is basically equivalent to Rudolf Steiner’s Spirit-Self.